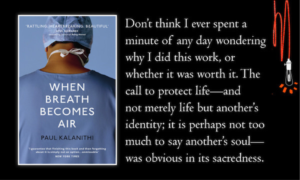

For a second time, I’m reading When Breath Becomes Air by surgeon and author Paul Kalanithi. At age 36 and on a career path that was spiraling upward, Dr. Kalanithi was rudely interrupted. By a lung cancer diagnosis.

I had originally highlighted several passages in the book, but one that stood out the second time around was this:

“Sitting in [the therapist’s] windowless office, in side-by-side armchairs, Lucy [Kalanithi’s wife] and I detailed the ways in which our lives, present and future, had been fractured by my diagnosis, and the pain of knowing and not knowing the future, the difficulty of planning, the necessity of being there for each other.”

This is how it is with a terminal diagnosis. My husband was given two years. The doctor didn’t say, You, Gary Johnson, have two years of life left, but rather, On average, men your age and in your shape, but with late-stage disease can expect about two years.

So we knew our future together was limited, but we didn’t know exactly how much time we had together. Which is really the case for all of us, cancer diagnosis or not, right?

Consider these 5 steps for living with knowing and not knowing what the future holds:

Organize your business affairs.

Make sure all important paperwork is complete and updated: will, durable power of attorney, beneficiaries named on assets, advanced directives and/or Physician’s Order for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form.

In a WebMD article by Tom Valeo entitled “Putting Affairs in Order Before Death,” five steps are listed for what everyone should do before they die to make sure their families know what their wishes are, from funeral plans to end-of-life care.

This thought from Charles Sabatino, director of the American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging:

“I think there’s an emotional obstacle to this kind of planning. … the unspoken belief is that death is optional.”

It would have saved a lot of frustration had Gary and I known to put my name as primary on our accounts — bank, cell phone, web hosting, credit cards. In most cases, an electronic copy of my husband’s death certificate satisfied the place of business, but not until countless hours on hold with 800-numbered businesses. Once, while on the phone with a bank customer service rep, my credit card was cancelled immediately when she learned the primary name on the account was deceased.

Continue making future plans.

Had we taken Gary’s two-year prognosis as fact, we wouldn’t have established a non-profit. We wouldn’t have shared our story and survival tips to a variety of audiences across the country. As it turned out, Hubby lived ten years with late-stage disease. Ten burbling, adventurous, courageous years. Continue planning for a future together.

Create adventure and memories.

Our non-profit carried the mission of survivorship education for cancer patients and their caregivers. As we spoke in various regions of the country, we stayed a little longer on our own dime.

As a result, we hiked the Tetons, ran from Pacific waves, rambled through New England during leaf-changing season, toured lighthouses on North Carolina’s outer banks, peered over the rim of the Grandest Canyon, strolled the River Walk in San Antonio, drove across Alligator Alley, sampled lobster in Maine, came across a rather large bull elk on a trail in the Rockies, and explored the red red canyons of Arches and Bryce.

And I have the photos—mental and digital—that document all our fun-making and adventure-taking and memory-creating that can never be taken from me.

Have the important conversations.

My heart goes out to those who have lost a loved one tragically and unexpectedly, and didn’t have the opportunity to say the important things that needed to be said. Gary’s cancer was slow-growing, and we had all the time in the world to affirm our love and appreciation for each other, and to have all those important end-of-life discussions. So here’s the question: Why not take every opportunity today and tomorrow and all the next days to let our family and friends know what they mean to us?

Connect with hospice care sooner than later.

At a time when Gary opted out of further chemo, the oncologist suggested a referral to hospice care: “Up until this point, all the care has been focused on you,” he said to my husband. “But who’s taking care of her?” he asked, pointing to me. My eyes misted up.

Most people wait for a crisis before calling in the hospice care team. If the patient meets the requirements for a referral, even if he/she is feeling relatively well and still getting around, as in Gary’s case, it benefits both patient and caregiver to get plugged into hospice care services before a crisis.

* * *

For terminally-diagnosed patients and their loved ones, there is the pain of knowing the future – death, sooner than planned. And there is the pain of not knowing how to plan for the days ahead, not knowing how many there will be.

Plan anyway. Say all that needs to be said and live full-out anyway.