In the fall of 2022, my life was changed by a single phone call when I was diagnosed with stage II B-cell, non-specified, non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, a rare and aggressive cancer of the lymphatic system. For me, a large tumor was growing in my left armpit. The tumor was damaging my ulnar nerve to the point that for more than a year my pinky and closest finger always hurt with a painful electric shock that never went away. I also lost feeling and most of the use of both fingers. As the mass grew, the pain and intensity increased. One local doctor thought it was a simple case of nerve impingement, something, perhaps in my elbow, was constricting the nerve and causing the pain. Another thought it was arthritis and gave me an anointment. Another thought it was related to my weightlifting in the gym, so he told me to stop lifting heavy weights. Finally, after seeing three different local doctors who kept misdiagnosing my condition, I was referred to a specialist in a larger city who in short order ordered an MRI, a biopsy, and a PET scan. Within days, I was told that I had cancer and that I would be dead in three months if I did nothing. From that moment, I began my arduous journey down the foot-worn path trod by many before me, asking questions such as “Why me?” and “What did I do to deserve getting cancer?”

Fortunately, I was told that my cancer was curable with chemotherapy and immunotherapy. But because of the nature and the size of the tumor, my treatment had to be immediate and aggressive—only the strongest chemo would knock down the cancer. Days after receiving the diagnosis, I was admitted to the Ellis Fischel Cancer Center at MU Health in Columbia, Missouri. For the next half year, I spent a week in the hospital every month in the very capable hands of doctors, nurses, radiologists, techs, and other staff. During that time, my own mortality was never far from my thoughts. All I had to do was to look in the mirror to see death lurking over my shoulder. Fortunately, the cancer responded positively to the chemo. A second PET scan between the third and fourth cycles revealed that the tumor was totally gone. I was, in effect, cancer-free. But, to be safe, I’d have to endure a few more cycles of chemo to make sure the lymphoma did not return or manifest elsewhere in my body. To prevent it from lodging in my brain, I endured numerous intrathecal injections of a specialized chemo into my lower spinal disks.

Instead of maintaining a journal as some patients do, I decided from the day I received my diagnosis that I would write down my thoughts, concerns, fears, experiences, and tribulations as poetry. After all—as I often remind my students—the sheer act of writing poetry is the compulsion to express ourselves, even in, and especially in the face of our own demise. As best I could, I arranged the poems chronologically to tell the story as it unfolded. As far as I know, there is no other book like it.

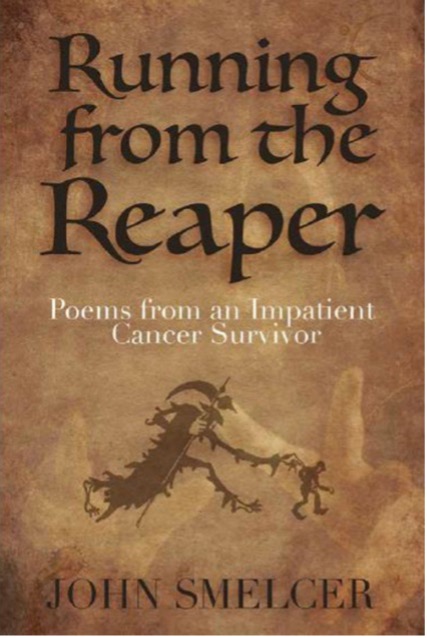

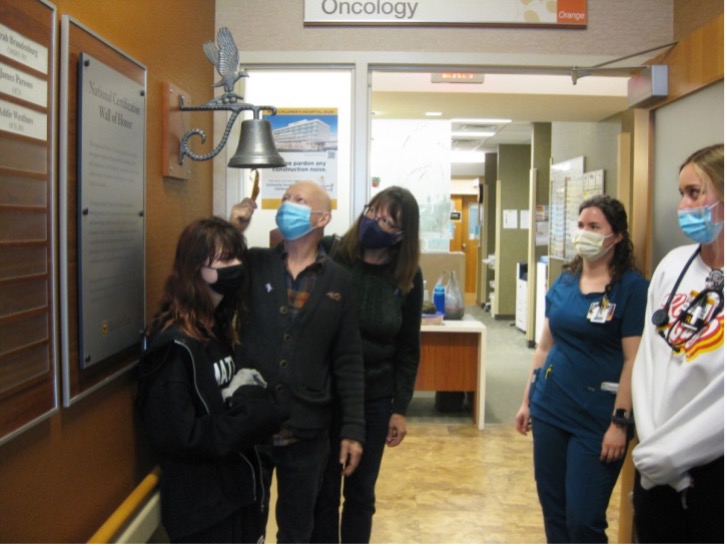

The subtitle of Running from the Reaper, Poems from an Impatient Cancer Survivor, comes from my reluctance to undergo my sixth and final treatment. After five cycles of chemotherapy, I was sick and tired of the hospitalizations and my body’s rollercoaster ride of ruin and recovery. I argued fervently with the chief oncologist to let me be done. I implored him, “Is there any medical evidence that six cycles is significantly better than five?” Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed and I completed all six cycles (mostly for my family’s sake). I am happy to say that on an unseasonably warm day in early February 2023, I got to “Ring the Bell” on the Oncology ward, signaling the successful completion of my cancer treatment. The long and uncertain road of recovery lay ahead of me.

Two months after I rang the bell, according to protocol, I had a follow-up PET scan to make sure the cancer hadn’t returned. I’m happy to say the results were negative—nothing suspicious was detected. My cancer is gone. The only trace that it ever existed is these poems. I’m pleased to share three of them from the collection:

On Receiving Results of a Biopsy

“Cancer,” she said before hanging up.

And just like that my world was shattered.

A single word,

the one they told me I probably wouldn’t hear.

“If it was cancer,” the previous doctors had said,

“it would be bigger by now and you’d be in more pain.”

But they were wrong. They were all wrong.

The woman on the phone said it was aggressive.

I don’t like the sound of that.

For a long time I sat with the phone in my lap,

stunned, mumbling the word over and over,

each time the word becoming more real,

my future less certain, as if I was standing before a cavern.

For the first time in my life, I understood

the way Noah must surely have stopped his labor

from time to time, wiped his sweaty brow,

and gazed fretfully at the dark, roiling clouds.

The Fighter

Folks always say that people diagnosed with cancer are “fighters.”

“He’s fighting cancer,” they say.

But I’m not so sure.

I just finished my second cycle of chemo—

a week in the hospital both times.

I’m no fighter. I’m a surrenderer.

I just lie in bed giving in to the cure

letting the doctors and nurses put whatever they want into me:

Hang another bag of chemo,

swallow a heap of pills,

roll over for a spinal infusion.

“We’re killing you to save you,” they remind me every day.

And they’re not lying. I’ve lost ten pounds already. All muscle.

I’m no fighter.

I’m just a little, frail, balding, and frightened old man

lying in my sick bed waving a little white flag

torn from my pillow.

Chemo Cycle Blues

I was brushing my teeth this morning

when I looked up after spitting.

There in the mirror was a bald man

holding a toothbrush, his eyes

full of bewilderment and incredulity,

his face pallid and gaunt,

his eyes deeply sunken, lips chapped,

his beard and hair gone.

I leaned closer to the glass to better glimpse

the stranger holding my toothbrush.

In all my life, I never imagined I’d write a book like this. Who would? But once the process began, the poems came out of me faster than anything I’ve ever experienced. It was magic. Or maybe I should say it was medicine, good medicine. The poems were genuine and human, full of strength and weakness, humor and despair, doubt and faith. I, and others, believe that anyone who has cancer or cares for someone with cancer or who loves someone with cancer should read this book. You can order the book online here.

John Smelcer, PhD is the author of over 60 books, many translated into other languages. His writing appears in hundreds of magazines worldwide. From 2016 to 2021, he was the Inaugural Writer-in-Residence for the Charter for Compassion, the world’s most comprehensive movement for peace and compassion. Every spring, Dr. Smelcer teaches a global online course called, “Poetry for Inspiration and Well-Being.”